"So what's wrong if I had? Or I did? Would I be guilty of something? If I like it I'll do it. We have a great actor in France named Michel Simon and Michel Simon said once, "If you like your goat, make love with your goat." But the only matter is to love."

Alain Delon, on his alleged homosexual tastes (1969)

And that's where M. Delon should have left it...in the full knowledge that actors' 'truths' about themselves are often to be taken with the same grain of salt as speculation about their sexuality. But he didn't. With his more recent dotage he's become the proverbial whore in church spouting homophobia while writing fluffy books about the women he's loved. His claim to not be bothered about being wrong can be interpreted as evolved masculinity or next-level narcissism. Richly deserving of the 2019 Cannes Palme d'Or d'Honneur for his body of work, it's hard to argue that he didn't also earn some of the backlash and personal denouncements his award attracted. It was full-circle for Alain Delon: he'd first shown up at Cannes in 1956 as the escort of an older actress, rather than as an actor. According to Roger Ebert he nevertheless walked the red carpet with gay star (and lifelong friend) Jean-Claude Brialy.

A Real Piece Of Work

Even as his millions of fans have tacitly accepted every salacious and unsavory aspect of his life, so they've accepted many probable dalliances with men - be they for love or personal advancement. Or as Claudia Cardinale put it: "Alain Delon? Men and women were lining up to have sex with him." But no amount of vilification or self-promotion can ever destroy or create the work of art that simply is. Delon's on-screen magnetism was summed-up many moons ago with a simple and succinct comment: "You just didn't know whether he intended to kiss you or kill you."

The Style And Substance Of Homoerotica

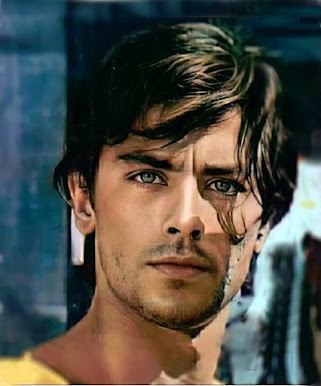

|

| When nobody else finds you attractive or desirable |

No amount of lived experience as a unisex object of desire could prepare Alain Delon for René Clément's Plein Soleil / Purple Noon (1960). The lead role in the first filming of "The Talented Mister Ripley" required acting skills far beyond what excellent direction could declare as believable. At twenty-four, Delon delivered a bullseye performance as the otherworldly Tom Ripley - seamlessly demonstrating pathos, menace and sexual ambiguity of the mostly creepy kind. A risky role, it fell to the amorphous quality of star power to succeed. The camera sent Alain Delon directly to the imaginations of audiences - any and all disparate gazes perceived exactly what their psyches craved. As we swoon we ignore the fact that nobody in the film finds Tom Ripley particularly attractive.

Originally up for the much easier second male role of the cruelly masculine Phillipe, Delon coveted the lead and his pitch to Clément and the producers (who humiliated him as "a little prick who should pay to be in the film") was that he shared Ripley's character. Watching Alain Delon in Plein Soleil does little to support any counter-arguments.

The role also demanded style, which Delon expertly served up as suave stardom, rather than something of an actor in good wardrobe. Well into the 21st Century, men's fashion writers globally invoke Delon as Ripley to demonstrate what style is, as they peddle expensive retro-ish fashion to men pursuing the myth of the alpha male with no regard for the amusing sidebar fact that they're being urged to impersonate an impersonator.

Commerce sometimes picks up on good ideas, and French style done properly gives a man an enigmatically attractive edge when being like him and being with him become blurred as sublimated homoerotic feelings. Of course, there would be no more aggressive salesman of Alain Delon Style than Alain Delon himself, as he merchandised as many aspects and accoutrements of his potent youth as possible through an endlessly extended middle-age.

A Piece Of Work In Progress: The Visconti Factor

The homosexual gaze as passively experienced is one thing. The homosexual gaze as artistic inspiration and motivation is something else again, with few willing to acknowledge that some of the greatest art of Western civilization is the creation of homosexual men. Or that it was so before the term was even invented and pathologized. Luchino Visconti didn't make gay movies per se - the highly-educated aristocrat's cinema is as obtuse as it is rich in its social commentary while appearing unconfined to stylistic considerations.

Neither dissolute playboy nor self-absorbed trained actor waiting for breaks, Alain Delon immediately grasped all that cinema is, and set about being a great star actor within the collaborative process. His appetite and respect for great direction paved the way for what he had to be and do when chosen by Luchino Visconti as the titular lead in Rocco e i suoi fratelli / Rocco And His Brothers (1960). While Plein Soleil went a long way to establishing the Delon stereotype, Rocco as conceived by Visconti is an allegorical opposite. He's arguably the most womanly manly male ever to grace a cinema screen. While he could box with the best of them, Rocco's saintlike character is entirely of female components like tenderness, loyalty, protection, sentiment and sacrifice. Visconti clued us up early in the piece by sending Rocco out in the cold to happily do labor in his mother's sweater.

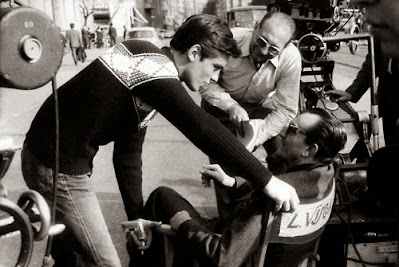

|

| Taking direction or asserting intimate territory? |

|

| No faked period makeup for Tancredi |

|

| On the 'Il Gattopardo' set (1962) |

A Body Of Work, The Scent Of A Man

|

| Delon's notorious swimwear getup for 'The Yellow Rolls Royce' (1964) |

Hollywood never knew what to do with Delon, but nevertheless took a shot at imagining what a Frenchman wore for a swim. Never bulge-friendly, MGM wasn't so shy about taking the tits-and-ass approach. While The Yellow Rolls Royce hasn't achieved any measure of esteem after the fact, the same can't be said of Delon's black terry-cloth trunks: a decade ago at auction a version attracted four times their estimated value. The following year, The New York Times review of Once A Thief took a veiled and bitchy pot-shot at his masculinity by declaring he "appears to be a romantic intellectual, and not a rough-tough type". While Delon's masculinity was at odds with Hollywood's male all-American graceless lumpiness, it resonated with men of the Far East: in a long-shot he passes as an Asian male ideal and that ensured a lifetime of idolatry and superstardom in territories east.

Alain Delon's failure to resonate in a slew of Hollywood films didn't stop Jean-Pierre Melville creating an apparent vehicle for him. Without seeing one line of a script Delon committed to 1967's Le Samourai. A mutual trust exercise, Melville's invasive camera wanted much more than star-power - it demanded the acting chops of a man who could create a hired killer unanchored to morality or temporal references. Delon's Jef Costello is indeed a very real man of existential loneliness. He surrounds himself with no spoils of war and has to share a girlfriend. His eccentricities (a fedora, white gloves, a bird) flesh out a character which will have to carry the movie, with no action sequences to help him out. In purging Jef of machismo and obvious heterosexuality, Melville put a man on the screen who still resonates with men everywhere. Many a movie has been subsequently borrowed from Jef Costello: the fact that Alain Delon could summon him at the age of thirty-one is astonishing

|

| The still from 'La Piscine' which informs its modernized artwork, and then some |

Sexualized Delon in a Courreges bathing suit however still sells La Piscine (1969). In fact, it still sells not only the movie but a whole lot more: in 2010 Alain Delon became the face of Eau Sauvage when Dior relaunched the sensational 1966 men's perfume. Vintage 60's photos of Delon in print ads, and a TV commercial of clips from the aforementioned film, heavily feature Delon in the aforementioned swimsuit. Eau Sauvage was our bourgeois gateway to the Houses of Guerlain and Sisley, and it's only appropriate that Alain Delon being of the senses takes us to that place when and where the world is sensed as better, with just a dash of something like class.

On a good day it's easy to part the mists of Avalon à la recherche du temps perdu, and be on a sun-drenched Mediterranean with a man who excites our senses...all of them. He looks good, he smells good, he infuriates us, he impresses us, he indulges our projections and we're more alive for the experience. He's insouciance and he mixes a damned good Boulevardier. You may have met him in Saint-Tropez but then again you may have met him in the brig. He's probably Alain Delon.